PolyMet Mine: Environmental Injustice

Environmental justice is the basic principle that tribes, low-income communities, and minority communities should not bear a disproportionate burden of the environmental harms resulting from a proposed government permit, approval, or action. Environmental justice is reflected in federal executive orders and federal case law:

- Executive Order 12898 (February 11, 1994) directs each agency to “make achieving environmental justice part of its mission by identifying and addressing, as appropriate, disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of its programs, policies, and activities” on minority populations, low-income populations and federally recognized Indian tribes. “Agencies are further directed to identify potential effects and mitigation measures in consultation with affected communities.”

- Executive Order 13045 (Apr. 21, 1997) requires any environmental review to determine environmental justice harms, including “the potential for multiple exposures or cumulative exposure to human health or environmental hazards in the affected population, as well as historical patterns of exposure to environmental hazards.”

- The federal government also has a fiduciary obligation to protect Tribal federally reserved rights under more than a century of case law.

– Ricky DeFoe, Ojibwe Pipe Carrier & WaterLegacy Board Member

The PolyMet sulfide mine would result in environmental injustice. Although agencies may have communicated with tribal staff and experts during environmental review and permitting, from WaterLegacy’s perspective, substantive consultation to resolve major tribal concerns about the PolyMet sulfide mine did not happen.

Disproportionate Impacts: Treaty Reserved Rights

The PolyMet sulfide mine pits, processing plant, waste disposal sites, and transportation and utility corridor would all be located in Ceded Territories in which the Ojibwe have retained rights to hunt, fish, and gather plants under the 1854 second Treaty of La Pointe. In this Treaty, the Ojibwe ceded most of the land on the northern and western shores of Lake Superior to the U.S. Government. The 1854 Treaty also established the Grand Portage and Fond du Lac Reservations of the Chippewa (Ojibwe).

As the Fond du Lac Band commented in opposing the PolyMet Land Exchange,

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Army Corps) approved the PolyMet wetlands destruction permit even though it admitted that the mine would cause harm to exercise of treaty rights:

Burden of Mercury Contamination of Fish

The PolyMet mine, processing plant, and waste rock piles would also be located in the headwaters of the St. Louis River, on which the Fond du Lac Reservation is located. The Fond du Lac Band has adopted – and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has approved – water quality standards for its Reservation waters, including a stringent standard to prevent mercury contamination of fish. The segment of the St. Louis River within the Fond du Lac reservation violates both Minnesota water quality standards and Fond du Lac water quality standards.

The Army Corps accepted PolyMet’s assumptions regarding its own pollution and discounted tribal analysis in approving the PolyMet Final EIS. But, the Army Corps admitted:

The weight of scientific and public health evidence from tribal scientists, wetlands and mercury experts, and Minnesota medical professionals demonstrates that the PolyMet mine project would increase mercury contamination of fish, disproportionately and negatively affecting Ojibwe people who rely on fish for subsistence.

Cumulative Effects

The Fond du Lac, Grand Portage, and Bois Forte Bands requested a comprehensive Cumulative Effects Analysis of the harmful impacts on Tribes and Tribal Lands using current U.S. Environmental Protection Agency federal guidance.

Despite the Bands’ official role in environmental review as Co-operating Agencies, the state and federal Co-Lead Agencies did not resolve either in the Supplemental Draft EIS or in the Final EIS even the most fundamental concerns identified by the Fond du Lac and Grand Portage Bands and their scientific consultants years before. For many of the Tribal “Major Differences in Opinion,” the agencies merely said their “response remains unchanged.” For none of the Tribes’ major concerns did the FEIS provide the Tribes with an opportunity to make their own updated comments.

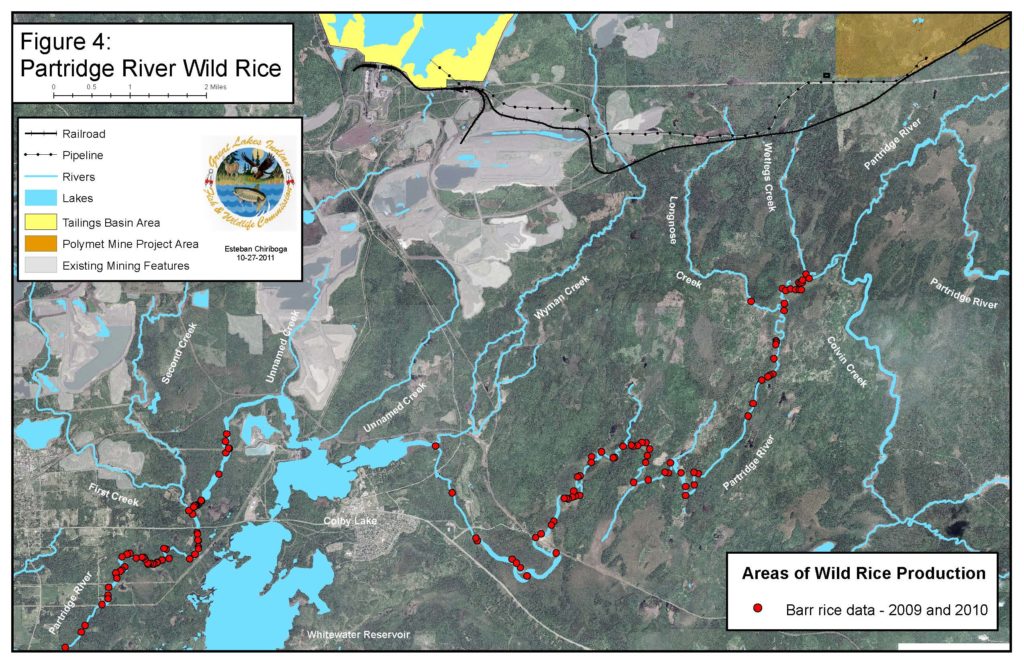

Wild Rice Waters

Draft MPCA Staff-Recommended Wild Rice Waters, PolyMet NorthMet mine project. Final EIS Figure 5.2.2-1.

Most troubling, neither the final NPDES/SDS water pollution permit, the fact sheet, nor the Findings of Fact, Conclusions and Order issued by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency on December 20, 2018, identify any wild rice waters downstream of PolyMet pollution. In fact, the NPDES/SDS water pollution permit doesn’t even use the words “wild rice.”